[Update: this post references a panel event at BristolCon which you can now watch at this link - from around 18'30" onwards - if you wanted to].

--------------------------

"PIXIES IN SPACE: Folklore and local legend have been a potent resource for fantasy literature for years, but could they also be a source of inspiration for SF?"

Any thoughts..? Yep, this post is me asking you to help me do my homework - in so far as, I'm on a panel tomorrow at Bristolcon and I feel like the least qualified person on it (I'm neither a published novelist, nor a well-known genre publisher and editor; I was the punchline of a cartoon in Banana Wings once, that's about it).

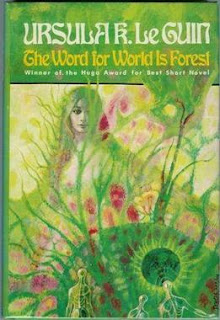

Depending what other participants - Anna Smith Spark, Rexx Deane & Cheryl Morgan (with Tom Toner moderating) - bring to the table and how we interact, I may end up talking about Ursula LeGuin (esp. 'The Word for World is Forest'), Ken MacLeod, Nnedi Okorafor, Nigel Kneale - and why Arkady Martine's 'A Memory Called Empire' is *better* than Isaac Asimov's 'Foundation'.

There might be a chance to tease out some of the different philosophical and moral implications of an interest in 'folklore' - clearly, some Very Good and also some Very Bad people have maintained an interest in folklore, mythology and legend; perhaps one could reverse into the subject by way of talking about folklore's actual or presumed detractors and haters, beginning with Plato and ending with the likes of Ray Kurzweil and Max Tegmark (following the Rapture of the Nerds, or the transformation of all of the Universe's matter into computronium, what use would there be for it?).

('Close Encounters of the Third Kind' is, incidentally, a kind of Neoplatonic 'Pilgrim's Progress' story - one of the first descriptors of the alien spacecraft is by a desert-dweller who says that "the sun came out at night and sang to him”; we all remember the sun as symbolising the highest form of the Good in Plato; Roy Neary's quasi-religious devotion to his quest is then a ladder which lifts him from his mundane life and which he then kicks away in order to ascend into a mystical union with the cosmos).

There's also teasing out the tension inherent in two possible overlapping definitions of 'folklore': "the traditional beliefs, customs, and stories of a community, passed through the generations by word of mouth AND a body of popular myths or beliefs relating to a particular place, activity, or group of people (e.g. ‘Hollywood folklore’)" - where one shades into the other is, in a way, a mere question of timescale.

So: one reason I like Ken MacLeod's books is that he conveys a sense of the way that political belief systems, information technology, science fiction itself are all cultures that - while positing themselves as coolly rational - also accrete (and/or reproduce themselves as) 'folklore'. This kind of anthropological approach matches my own 'felt sense' of political affiliation as tribal as well as rational - drop me into either a Labour Party gathering or, more so, a Green Party get-together and there's the sense of breathing more easily, being more 'myself', by virtue of having any number of shared reference points, stories, perspectives, even jokes; set me down amongst Lib Dems, football fans or chess afiocandoes, less so (communication would then become a more conscious effort).

Then there's a definitional question about 'folklore' - the majority of people who have ever lived have, perhaps, been unaware of 'folklore' in the same sense in which a Victorian gentleman would've been unaware of owning an *analogue* watch - what other kind of portable timepiece, what other way of knowing and interpreting the world *could* there be? By definition, if we're positing folklore *as* folklore, we're already hold a certain 'outside' perspective - and we find ourselves looking back with, what? Regret? Longing? Curiosity? The impulse to preserve, or collect?

And, last but not least, 'local legend.' These sound quaint, harmless, a tale told to children around the fire when the day's work is through. However, 'local legends' can grow large enough to act in history: think the apocryphal Leicestershire weaver Ned Ludd, later General or even King Ludd (some stories just grow in the telling - and there's plenty to say about the absent, exiled or sleeping 'Good King' as a kind of folkloric 'strange attractor'). Gavin Mueller's 'Breaking Things at Work: Why the Luddites Were Right About Why You Hate Your Job' documents the surprising persistence of his spirit into the tech cultures of the 1980s, 1990s and beyond - but has anyone blasted the Good General into space yet..?